Finnish Face of Fascism | RT Documentary

Keep up to Date & Bypass the Big Tech Censorship

Get uncensored news and updates, subscribe to our daily FREE newsletter!

During World War II, Finland was Germany’s ally. Nazi ideas thrived among the Finnish leadership, who developed a theory of racial superiority. According to historian Sergey Verigin, at the beginning of the 20th century, radical circles tackled the idea of establishing the Greater Finland state, which would include all Finno-Ugric nations.

The Finnish administration introduced military order in Soviet Republic of Karelia. Finns divided the population of occupied Soviet Karelia into ‘citizens’ and ‘non-citizens.’ Citizens were people of Finnish and Ugrian origins. They received shelter, jobs, and ration cards. All other nationalities, mostly Slavs, were superfluous to Greater Finland.

“Mannerheim issued order No. 132 with a clause stating: put Russians in concentration camps. Karelia hadn’t fallen, but the Karelians’ fate had been decided: Russians put in camps and then expelled. They wanted to wipe out every Russian, ” says Sergey Verigin, PhD, Director of the Institute of History at the Petrozavodsk State University. “In 1941, they went further than just reclaiming their lost territories. They occupied almost all of Karelia. Petrozavodsk was never Finnish, or Zaonezhye. They’d been Russian for centuries, they captured them too.”

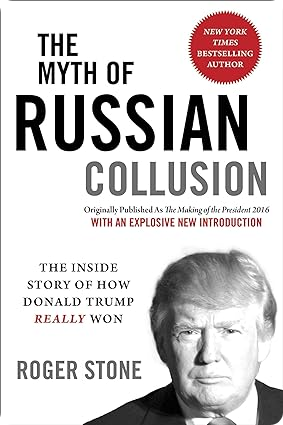

| Recommended Books [ see all ] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|

From 1941 to 1944, the Finns built 14 concentration camps, 34 labor camps and dozens of prisons in Karelia. Approximately 25,000 people went through the archipelago of Finnish camp, according to official figures.

Prisoners recall that every day they had to work for 10 to 12 hours and there was a terrible famine. Klavdia Nyuppieva, who survived the camp, recalls that her family of seven people had just seven spoons of flour per day.

The mortality rate in the Finnish concentration camps was even higher than in the German ones. However, the exact number of people who perished in Karelia and Petrozavodsk’s concentration camps is still unknown. That is why Finnish concentration camp survivors formed the Union of Former Juvenile Prisoners. Since 1990, the Society’s members have been seeking justice. Is it still possible to find the perpetrators after all these years?